Here I’ll drop the evidence I used in my latest video on Hitler and Stalin mutually admiring each other because they were so similar personally and politically as socialist totalitarians.

The Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was a non-aggression pact between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union with secret protocol that partitioned Central and Eastern Europe between them. The pact was signed in Moscow on 23 August 1939 by German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop and Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov[1] and was officially known as the Treaty of Non-Aggression between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.[2][3] Unofficially, it has also been referred to as the Hitler–Stalin Pact,[4][5] Nazi–Soviet Pact[6] or Nazi–Soviet Alliance.[7]

From “How Adolf Hitler Began to Admire Josef Stalin“:

Adolf Hitler’s assessment of the Soviet Union and Josef Stalin demonstrates the contradiction between National Socialist propaganda and Hitler’s actual opinions. While he never tired of attacking the “Jewish-Bolshevist conspiracy” in his speeches, from no later than 1940 onwards he changed his opinion: Stalin was, in Hitler’s eyes, no longer the representative of “Jewish interests” but was now pursuing a nationalistic Russian policy in the tradition of Peter the Great.

Hitler first alluded to the possibility of such a development in his “Second Book,” which he wrote in 1928, but was never published: However, it is conceivable that in Russia itself an inner change within the Bolshevist world could take place insofar as the Jewish element could perhaps be forced aside by a more or less Russian national one. Then it could also not be excluded that the present real Jewish-capitalist-Bolshevist Russia could be driven to national-anti-capitalist tendencies.

What Hitler later stated as a fact, namely Russia’s change from a “Jewish dictatorship” into a national Russian anti-capitalist state, he described in 1928 as being a possibility and a tendency. It is difficult to determine when Hitler finally revised his assessment of the conflict between Stalin and Leo Trotsky and came to the view he later constantly advocated, that Stalin had emancipated himself from the Jews and was pursuing a national and anti-Jewish policy.

Hitler’s minister of propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, reported in his diary on January 25, 1937, that Hitler had not yet completely made up his mind about the events in Russia and his assessment of Stalin:

In Moscow another show trial. This time solely against Jews again. Radek etc. Führer still doubtful whether not with hidden anti-Semitic tendency after all. Perhaps Stalin wants to drive the Jews out after all. The military is also supposed to be strongly anti-Semitic. Therefore keep eyes open. For the time being remain in wait and see position.

From early 1940 onwards, however, there were an increasing number of statements made by Hitler in which his admiration for Stalin and the Bolshevist regime become clear. These, no doubt, also served the purpose of defending the pact he had concluded with Stalin in 1939. But even after the attack on the USSR, when Hitler no longer had an alliance to justify, he clung to his positive assessment of Stalin. On September 23, 1941, Sturmabteilung (SA) Standartenführer Werner Koeppen noted the following statement by Hitler:

Stalin was one of the greatest of living men because he succeeded in forging a state out of this Slavic family of rabbits, albeit only with the harshest of compulsion. For this he naturally had to avail himself of the Jews, because the thin Europeanized class which had formerly carried the state had been exterminated, and these forces would never again grow up out of the actual Russianhood.

Of course, this assessment did not prevent Hitler from continuing to spread the thesis of “Jewish Bolshevism” in his speeches for propaganda purposes. But in contrast to these public propaganda statements, Hitler said in a table talk in early January 1942 that:

Stalin is seen as the man who had intended to help the Bolshevist idea to victory. In reality he is only Russia, the continuation of Tsarist pan-Slavism! For him Bolshevism is only a means to an end. It serves as a camouflage vis-à-vis the Germanic and Romanic nations.

On July 24, 1942, he claimed that “in front of Ribbentrop Stalin had made no bones at all about the fact that he was only waiting for the moment of maturity of their own intelligentsia in the USSR in order to make an end of the Jewry he still needed today as a leadership.”

Henry Picker, who recorded Hitler’s table talks, reports on numerous further talks in which Hitler expressed his admiration for Stalin or defended him against critical remarks. Hitler had always, for example, become angry when someone called Stalin a former “bank robber.” Hitler would then immediately defend Stalin with the declaration that Stalin had not carried out his bank robberies as a private person nor for the benefit of his own pocket, “but as a revolutionary and in order to finance the Communist movement.” For Stalin, Hitler said on July 22, 1942, “one has to have respect in any case. In his way he is quite a brilliant chap!”

Heinrich Heim, another witness who recorded Hitler’s table talks, also noted many positive statements by Hitler about Stalin. On August 26, 1942, Hitler said:

If Stalin had continued to work for another ten to fifteen years Soviet Russia would have become the most powerful nation on earth, 150, 200, 300 years may go by, that is such a unique phenomenon! That the general standard of living rose, there can be no doubt. The people did not suffer from hunger. Taking everything together we have to say: They built factories here where two years ago there was nothing but forgotten villages, factories which are as big as the Hermann Göring Works. They have railways that are not even marked on the maps. Here with us we argue about the tariffs before the railway is even built. I have a book about Stalin; one has to say: That is an enormous personality, a real ascetic, who has brought that huge empire together with an iron fist. Only when someone says that is a social state, then that is a gigantic swindle! It is a national capital state: 200 million people, iron, manganese, nickel, oil, petroleum and what you like – unlimited. At the head a man who said: Do you think the loss of 13 million people is too much for a great idea?

The things Hitler admired in Stalin become particularly clear in this statement: the consistency, even brutality (“iron fist”), with which Stalin—even with the sacrifice of millions of people—implemented the “great idea” and created a powerful industrial state impressed Hitler. In Stalin, he saw his own reflection, namely the executor of the dictatorship of modernization who did not shrink from the employment of even the most brutal methods.

Scheidt, who, as adjutant to Hitler’s “representative for military history” Walther Scherff and a member of the Führer Headquarters group, had close contact with Hitler and sometimes even took part in the “briefings.” Scheidt writes in his notes:

Hitler began secretly to admire Stalin. From then on his hatred was determined by envy … He clung to the hope that he could defeat Bolshevism with its own weapons if he copied it in Germany and the occupied regions … He increasingly held the Russian methods up to his associates as being exemplary. We cannot fight this battle for existence without their hardness and ruthlessness, he was wont to say. He rejected any objections as being bourgeois.

After July 20, 1944, for example, Hitler bemoaned the fact that he had not purged the Wehrmacht like Stalin had and converted it into a National Socialist revolutionary army. Hitler’s architect Albert Speer reports on a meeting of ministers on July 21, 1944:

Today he [Hitler] realized that in his case against Tuchatshevsky Stalin had taken the decisive step for a successful waging of the war. By having liquidated the General Staff he had made room for fresh forces, who no longer stemmed from the age of the Tsars. He had formerly always held the accusations at the Moscow trials of 1937 to be trumped up. Now, after the experience of 20 July he was wondering whether there had not been something to them after all. While he did not have any evidence for it, Hitler continued, he could still no longer exclude a treasonable co-operation between the two general staffs.

Two months before the assassination attempt, in a presentation to generals and officers, Hitler had said:

This problem has been completely solved in Bolshevist Russia. Completely unequivocal situations, clear unequivocal statements by the officer to these points of view, which concern the state, to the whole of expert opinion and with this, naturally, an unequivocal relationship to allegiance, a completely clear relationship. In Germany this whole process was unfortunately interrupted much too quickly by the war, because you can be sure that these courses which take place today would perhaps never have become necessary if the war had not come about.

What Hitler, therefore, primarily admired in Stalin was his revolutionary consistency in the elimination of the former élites. Hitler’s admiration for Stalin was not only an expression of the respect he felt for him personally; his relationship with Stalin also reflected his ambivalent position on Marxism/Communism, which was always characterized by simultaneous fear and admiration. Hitler admired Stalin’s revolutionary consistency above all, but exactly this consistency, which went far further than his own, also made him afraid, and made Bolshevism appear as the only serious opponent.

The fact that Hitler privately said that Stalin had eliminated the Jewish members of his regime and thus “Russified” Bolshevism itself undermines Hitler’s own war propaganda that he invaded Russia to “liberate” it from “Judeo-Bolshevism”. According to Hitler, Stalin had already done that job for him by the early 30s.

From Ian Kershaw’s “Hitler: Nemesis”:

‘Alluding to Mussolini’s letter in January, and to his own reply a few days before the meeting, Hitler emphasized how British intransigence had forced him to conclude an alliance with Russia. But, although Stalin had deprived Bolshevism of its Jewish and international character and turned it into a ‘slavic Moscowitism’, Russia remained for Germany an ‘absolutely foreign world’. ‘For Germany only one partner came into question: Italy. Russia was only insurance cover.’

From “How Hitler Became a Believer in the State-Planned Economy”:

to a certain extent we can only speculate on Hitler’s true position before 1933 because Hitler kept his plans strictly secret, primarily in order not to offend the businessmen. In his talks with Otto Wagener, the chief of the economic policy section of the NSDAP, Hitler underlined the importance of keeping his economic plans secret time and again. In September 1931, for example, he said:

“The conclusion from this is what I have said all along, that this idea is not to become a subject for propaganda, or even for any sort of discussion, except within the innermost study group. It can only be implemented in any case when we hold political power in our hands. And even then we will have as opponents, besides the Jews, all of private industry, particularly heavy industry, as well as the medium and large landholders, and naturally the banks.”

In speeches to industrialists before 1933, Hitler presented himself as a supporter of private ownership; in other speeches, he sharply attacked capitalism. Often tactical considerations played a role, and sometimes he was only saying what he knew his audience wanted to hear. One thing is certain, however: Hitler’s main intention was obviously to reconcile the advantages of the principles of competition and selection (in the socio-Darwinistic sense) with the “advantages” of a state-controlled economy.

So we can see here that before getting into power, Hitler’s Machiavellian tactic was to feign different positions to different audiences on this question. In front of lower class workers, he’d preach anti-capitalism; in front of a room of business owners, he preach anti-communism. But he was really fooling the business owners not the workers as we shall see.

More from previous source:

While the state was to direct the economy according to the principle “common interest before self-interest” and to set the objectives, within this framework the principle of competition was not to be abolished, because in Hitler’s view it was an important mainspring for economic development and technical progress. What was important, however, was that Hitler did not share the beliefs of economic liberalism, according to which the common good would come about as a result of the play of the various self-interests.

This is made clear in a speech Hitler delivered on November, 13 1930:

“In all of business, in all of life in fact, we will have to do away with the concept that the benefit to the individual is what is most important, and that from the self-interest of the individual the benefit to the whole is built up, therefore that it is the benefit to the individual which only makes up the benefit to the community at all. The opposite is true. The benefit to the community determines the benefit to the individual. The profit of the individual is only weighed out from the profit of the community…. If this principle is not accepted, then an egoism must necessarily develop which will destroy the community.”

In view of the successes then achieved by the economic policies of the government, Hitler’s reservations against state planning of the economy gradually diminished. How important Hitler considered the question of state-controlled planning of the economy to be can be seen from the fact that in August 1936 he personally wrote a “Memorandum on the Four-Year Plan 1936.” In this memorandum his admiration and fear of the Soviet system of planned economy were expressed: “The German economy, however, will learn to understand the new economic tasks, or it will prove itself to be incapable of continuing to survive in these modern times in which the Soviet state sets up a gigantic plan.”

Hitler was convinced of the superiority of the Soviet planned economy system over the capitalist economic system. This must be regarded as an essential reason why he so vehemently demanded and enforced the extension of state control of the economy in Germany as well.

Hitler attributed the success of National Socialist economic policy primarily to state control of the economy. From 1940 at the latest, Hitler increasingly became a proponent of the state planned economy – partly because he was convinced of the superiority of the Soviet Union and its economic system. In his monologs to his inner circle (known as “table talks”) on July 27-28, 1941 Hitler said that “A sensible employment of the powers of a nation can only be achieved with a planned economy from above.”

About two weeks later he said: “As far as the planning of the economy is concerned, we are still very much at the beginning and I imagine it will be something wonderfully nice to build up an encompassing German and European economic order.” The statement that as far as the planning of the economy was concerned one was still at the very beginning is important because it shows that Hitler was not thinking at all of a reduction of state intervention – not even for the time after the war – but, on the contrary, intended to expand the instruments of state control of the economy even further.

So here we see that by 1936, Hitler had thrust the economy into a mode of full-scale economic planning from above and that he modeled all of this on the Soviet Union. He later said that this state control of the economy was “only the beginning,” meaning that he was not planning to let off these controls after the war, he intended to keep them in place. That coincides nicely with two statements Hitler makes in 1934 and 1943 in which he calls outright for the elimination of “castes and classes” to equalize all Germans onto a level playing field:

“And we want that you, German boys and girls, to absorb everything that we wish for Germany. We want to be one people and through you, to become this people. We want a society with neither castes nor ranks and you must not allow these ideas to grow within you.” – Triumph of the Will (1934)

“All the more so after the war, the German National Socialist state, which pursued this goal from the beginning, will tirelessly work for the realization of a program that will ultimately lead to a complete elimination of class differences and to the creation of a true socialist community.” – Speech for the Heroes’ Memorial Day (1943)

More from Zitelmann:

On July 5, 1942 Hitler expressed the opinion that if the German economy had been able so far to deal with innumerable problems “… this was also due in the end to the fact that the direction of the economy had gradually become more controlled by the state. Only thus had it been possible to enforce the overall national objective against the interests of individual groups. Even after the war we would not be able to renounce state control of the economy, because then every interest group would think exclusively of the fulfillment of its wishes.”

Hitler’s view of the Soviet economic system apparently also changed from skepticism to admiration. In a table talk on July 22, 1942, Hitler vehemently defended the Soviet economic system and even the so-called “Stachanow System,” which it was “exceedingly stupid” to ridicule: “One has to have unqualified respect for Stalin. In his way, the guy is quite a genius! His ideals such as Genghis Khan and so forth he knows very well, and his economic planning is so all-encompassing that it is only exceeded by our own Four-Year Plan. I have no doubts whatsoever that there have been no unemployed in the USSR, as opposed to capitalist countries such as the USA.”

Hitler’s admiration for the Soviet system is also confirmed in the notes of Wilhelm Scheidt, who—as adjutant to Hitler’s “representative for military history” Walther Scherff and a member of the Führer Headquarters group—had close contact with Hitler and sometimes even took part in briefings. Scheidt writes that Hitler underwent a “conversion to Bolshevism.” From Hitler’s remarks, he says, the following reactions could be derived: “Firstly, Hitler was enough of a materialist to be the first to recognise the enormous armament achievements of the USSR in the context of her strong, generous and all-encompassing economic organisation.”

Scheidt writes that in view of such impressions Hitler had recognised and expressed “the inner relationship of his system with the so heatedly opposed Bolshevism,” whereby he had to admit that “this system of the enemy was developed far more completely and straightforwardly. His enemy became his secret example.” The “experience of Communist Russia,” particularly the impression of the alleged superiority of the Soviet economic system, had produced a strong reaction in Hitler and the circle of his faithful: “The other economic systems appeared not to be competitive in comparison.” About the impression of the rational organisation of farming in the USSR and the “gigantic industrial plants which gave eloquent testimony despite their destruction,” Hitler, says Scheidt, had been “enthusiastic”.

The German dictator admitted during a conversation with Benito Mussolini on April 22, 1944, he had become convinced: “Capitalism too had run its course, the nations were no longer willing to stand for it. The victors to survive would be Fascism, and National Socialism – maybe Bolshevism in the East.”

Hitler himself was convinced, as he emphasized in his last radio address on January, 30, 1945, “that the age of unrestricted economic liberalism had outlived itself.” These statements of Hitler’s in 1935 to 1945, but particularly from the beginning of the 1940s on, show that he had become a vehement critic of the system of free enterprise and a confirmed adherent of the system of a planned, state-controlled economy.

Operation Pike shows the extent of Soviet-Nazi collaboration worried the Anglo-French alliance:

Operation Pike was the code-name for a strategic bombing plan overseen by UK Air Commodore John Slessor against the USSR by the Anglo-French alliance.[2] British military planning against the Soviet Union occurred during the first two years of the Second World War, when, despite Soviet neutrality, the British and French concluded that the German–Soviet pact made Stalin an accomplice of Hitler.[3] The plan was designed to destroy the Soviet oil industry to cause the collapse of the Soviet economy and deprive Germany of Soviet resources, which, if successful, would have enabled Germany’s victory on the Eastern front. After the conclusion of the German-Soviet Pact, Britain and France became concerned that the Soviets supplied oil to the Germans.[4]

Volker Ullrich confirms Hitler’s private admiration for Stalin in “Hitler’s Downfall“:

“In the days that followed, much to the surprise of his lunch guests, Hitler continued to express his regard for Stalin. The Soviet dictator’s life resembled his own, he told them: the Georgian, too, had worked his way up from ‘an unknown man to the leader of a state’.”

From “When Stalin Was Hitler’s Ally”:

Between 1939 and 1941, as the Soviet Union presented Nazi Germany in its own internal propaganda as a friendly state, Soviet society ceased to criticize German policies and began to publish Nazi speeches. People in public meetings occasionally misspoke, praising “Comrade Hitler” or calling for “the triumph of international fascism.” Swastikas began to appear on buildings or even on posters of Soviet leaders.

David Irving reports the following in “Hitler’s War”:

“The next day, Papen also raised Stalin’s future with Hitler, and the Fiihrer repeated what he had told Goebbels a month before — that once the Wehrmacht had occupied a certain forward line in Russia, it might be possible to find common ground with the Red dictator, who was after all a man of enormous achievements. As another diplomat — Hasso von Etzdorf — noted: ‘ [Hitler] sees two possibilities as to Stalin’s fate; either he gets bumped off by his own people, or he tries to make peace with us. Because, he says, Stalin as the greatest living statesman must realise that at sixty-six you can’t begin your life’s work all over again if it will take a lifetime to complete it; so he’ll try to salvage what he can, with our acquiescence. And in this we should meet him halfway. If Stalin could only decide to seek expansion for Russia toward the south, the Persian Gulf, as he [Hitler] recommended to him once [November 1940], then peaceful co-existence between Russia and Germany would be conceivable.“

So Hitler was absolutely considering a world in which he could live in co-existence with Stalin if the Red Dictator had directed his own expansionism south and not west into lands Hitler wanted for German living space.

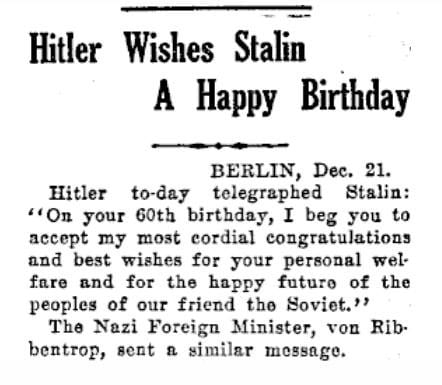

Hitler sent birthday wishes to Stalin in 1939:

Of the many books that deal with these two world-changing figures, “Hitler and Stalin: Parallel Lives,” by the British historian Alan Bullock, published in 1992, is the best — and certainly, at more than 1,000 pages, the most comprehensive. Bullock’s thesis is persuasive. Despite their differences in age, background and temperament — and despite their mortal enmity in World War II — there was a symbiosis, even an affinity, between the two: in their careers, their ideologies, their methods and their psyches.

They were both outsiders: the master of the Kremlin was a Georgian, not a Russian; the German Führer was an Austrian. Both, Bullock says, were narcissists. Both insisted on cults of personality and made themselves into high priests of warped versions of 19th-century social theories (Stalin’s Marxism, Hitler’s toxic combination of social Darwinism and the zanier ideas of Nietzsche). Both were homicidal paranoiacs, determined to deport, enslave and exterminate entire categories of human beings: in Stalin’s case, the kulaks during the collectivization campaign; in Hitler’s, not just Jews but Slavs, Romani and numerous others. Crucially, neither of these malevolent geniuses would have emerged from obscurity were it not for the first great cataclysm of the 20th century, then known as the Great War.

… As Bullock shuttles between his two subjects, he continues to refute commentators who have treated Stalinism and Nazism as diametrically opposed ideologies by labeling the first internationalist and the second nationalist. In fact, those terms were, in this pairing, a distinction without a difference. Both regimes were chauvinistic and expansionist, and both were police states with one-man rule and a reliance on terror, concentration camps and the Big Lie.

Hitler believed that the Third Reich would endure a thousand years. It lasted a dozen. For the first eight, he and Stalin, while geopolitical rivals, sometimes found common ground. Hitler’s minions admired and copied some of Stalin’s techniques of spying and liquidating enemies.

In 1939, much as Lenin and Kaiser Wilhelm had done, Stalin and Hitler made peace — though pre-emptively. They had their foreign ministers sign a pact guaranteeing that neither side would attack the other, while divvying up Poland and smaller countries. Late that year and into the next, the German Gestapo and the Soviet secret police, the N.K.V.D., held a series of conferences to coordinate their occupations.

Had Hitler held to that agreement, it is possible he might have won the war. Stalin might have sat out the conflict as it raged in the West, biding his time, then possibly consolidating with Hitler a condominium of totalitarian superstates.

What did happen was the Wehrmacht’s blitzkrieg into the Soviet Union in 1941, which caught Stalin by surprise. Why Hitler delivered this deadly but also dangerous blow, bringing new hope to Winston Churchill and the Allies, is still debated.

Bullock’s answer to that question came in his earlier biography of Hitler, who “invaded Russia for the simple but sufficient reason that he had always meant to establish the foundations of his thousand-year Reich by the annexation of the territory between the Vistula and the Urals.”

Known officially as the Treaty of Non-Aggression Between Germany and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, the Hitler-Stalin pact—signed 80 years ago Friday—stunned the world. Some said that by uniting implacable ideological foes it had turned isms into wasms.

That wasn’t quite right. As German negotiator Karl Schnurre had observed the month before, “despite all the differences in their respective worldviews, there is one common element in the ideologies of Germany, Italy and the Soviet Union: opposition to the capitalist democracies. Neither we nor Italy have anything in common with the capitalist West. Therefore it seems to us rather unnatural that a socialist state would stand on the side of the Western democracies.” Since capitalist democracy was their common enemy, why not pool resources?

Hitler and Stalin had demonized each other over several years, but they also had interlocking interests. Hitler wanted to invade Poland without fear of war on two fronts, so he had to neutralize the Soviets. He also needed access to Russia’s natural resources. Stalin coveted German industrial and weapons technology. To his cadre, he explained that he could destroy Germany later, after Hitler had assisted him in destroying the most “reactionary” imperialist capitalist countries, England and France. Though some balked, most communists world-wide acquiesced. Even the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm later acknowledged he’d had “no reservations” about it at the time.

Hitler invaded Poland on Sept. 1, 1939. Sixteen days later, so did Stalin, allegedly to “protect” the newly occupied “brothers of the same blood.” As revealed only after the war’s end, the dual move had been effectively sanctioned by a Secret Protocol accompanying the pact, which defined the borders of Soviet and German “spheres of interest” in Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Finland and parts of Romania.

Joseph Maiolo, a historian at King’s College London, wrote in 2014 that the arrangement “enabled the two regimes to experiment in brutal imposition of their ideological visions on the peoples of Eastern Europe.” British historian Roger Moorhouse, whose 2014 book, “The Devils’ Alliance,” incorporates recently released Soviet-era documents, amply demonstrates that “a remarkable symmetry emerged between the occupation policies adopted by the Nazis and the Soviets. . . . The two sides even employed similar tactics: deportation, hard labor, and execution.”

The devils’ alliance seemed cordial. In December 1939, Hitler wished Stalin on his birthday “a happy future with the peoples of a friendly Soviet Union.” Stalin responded with a toast to “the friendship between the peoples of the Soviet Union and Germany, cemented in blood.” But when Stalin occupied part Northern Bukovina, part of Romania, in the summer of 1940, Hitler is said to have flown into a rage. Hitler worried about the proximity of Soviet forces to the Romanian oil fields, which were indispensable to Germany. Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels wrote in his diary in early July 1940: “Maybe we will have to move against the Soviets after all.”

On June 22, 1941, they did. Stalin didn’t believe the intelligence warning of a German invasion. But he soon came up with a rationalization for his oversight: The pact had secured his country months of peace and provided “the opportunity” to rearm. That became the official line. The Secret Protocol, which revealed Stalin’s real strategy, was never mentioned. Rumors of its existence circulated, and an English translation was published by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Only in 1948 did the U.S. State Department release an official copy, alongside thousands of other documents seized from the Germans. Moscow issued a communiqué declaring it a forgery and itself “offended” at the “falsification of history.”

The second and third paragraphs stating that the Nazis had nothing in common with the “capitalist West” and thus were more tailored to break bread with the Soviet communists fits like a glove with what Zitelmann quoted from Hitler in 1944:

The German dictator admitted during a conversation with Benito Mussolini on April 22, 1944, he had become convinced: “Capitalism too had run its course, the nations were no longer willing to stand for it. The victors to survive would be Fascism, and National Socialism – maybe Bolshevism in the East.”

Historian John Lukacs informs us that Stalin liked and admired Hitler too and ignored dozens of clear intelligence warnings of a German attack believing his friend Hitler would never do so:

CONAN: And then there is Stalin. Universally described as shrewd and suspicious, canny, but who could not bring himself to accept overwhelming evidence that an invasion was about to happen.

Mr. LUKACS: He didn’t–there was more than one reason in his mind. One of them was obvious. He knew that, particularly Churchill would like to see a war between Germany and Russia. He believed it was in the British interest for that to happen. So he was with his usual suspicion–and also to some extent lack of profound knowledge of the western world–believed that much of this was machination, because Hitler, and this comes as a second element, would be foolish. It would be very unlikely for Hitler to start a war, a two-front war, when the one-front war is not at all concluded.

Now added to this comes a very important element that some people have known, and that’s Stalin had a liking for Hitler. Stalin greatly admired Hitler. The odd thing is that his respect and admiration for Hitler appeared in drips and drabs even after the war started, even toward the end of the war, here and there he dropped some quite comfortable remarks about Hitler, or rather he had admired.

And another element connected with this is that Stalin had a great liking and respect for Germans and for Germany. And that goes back to pretty early in his career.

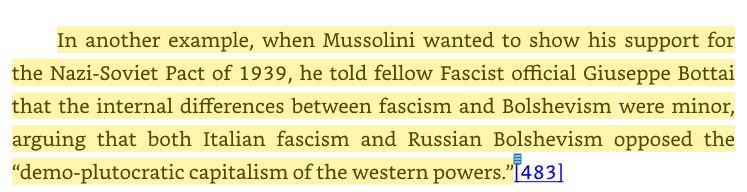

Mussolini made a similar statement to Hitler that the fascists had more in common with the Soviet communists than the “demo-plutocratic capitalism of the Western powers”. From “Killing History”:

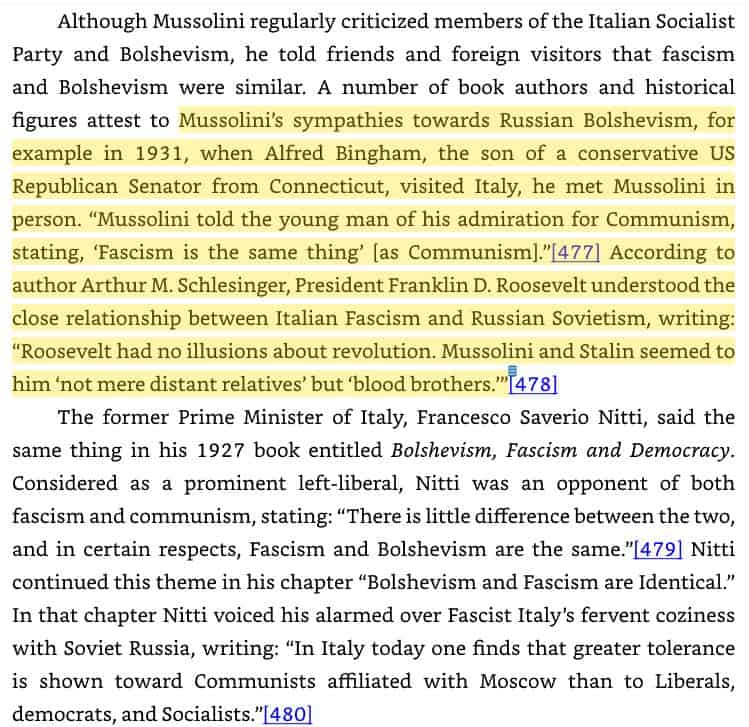

Time and again the National Socialists and Fascists tell us of their affinities for and similarities with communists. Here’s another from Mussolini, in which he told the son of a US Republican Senator, that “fascism is the same thing as Communism”:

Mussolini said Stalin was a “fellow fascist”:

Both Fascism and Marxist Communism created welfare-warfare states:

The infighting between fascists and communists was a brother war between ideological kin fighting for power:

By 1943 Mussolini was once again pronouncing his desire to eliminate what was left of free enterprise in Italy:

In 1933 speech Mussolini declared the “end of laissez-faire” and a march towards socialism:

In a Jan 30, 1945 address Hitler too proclaimed that he was done with free enterprise entirely and would move sharply towards Communism:

Hitler himself was convinced, as he emphasized in his last radio address on January, 30, 1945, “that the age of unrestricted economic liberalism had outlived itself.” These statements of Hitler’s in 1935 to 1945, but particularly from the beginning of the 1940s on, show that he had become a vehement critic of the system of free enterprise and a confirmed adherent of the system of a planned, state-controlled economy.

In the 1940s as his rule was coming to an end, Mussolini wrote anonymous articles calling for another bloody socialist revolution against capitalism (which he had already eliminated in Italy) and that his government was the only truly socialist one next to Soviet Russia:

Adolf Eichmann explained in his memoirs that he was just as much a radical socialist as a nationalist:

L. K. Samuels in “Killing History” describes Mussolini as a closeted Marxist who hated the monarchy and the Church:

Hitler and Mussolini praised FDR for his interventionist economic policies only to later decry him as a “capitalist” when they went to war:

Former Italian politician Nitti said that fascists are “revolutionary socialists”:

The Reich leadership referring to Gauleiter Eric Koch as a “second Stalin” as a compliment for his brutality in Ukraine:

“Opposing Rosenberg’s wishes, Hitler had yielded in the conference of 16 July to the suggestion of Göring, backed by Bormann, that the – even by Nazi standards – extraordinarily brutal and independent-minded Erich Koch, Gauleiter of East Prussia, should be made Reich Commissar of the key territory of the Ukraine. Koch, like Hitler, but in contrast to Rosenberg, rejected any idea of a Ukrainian buffer-state. His view was that from the very beginning it was necessary ‘to be hard and brutal’. He was held in favour in Führer Headquarters. Everyone there thought he was the most suitable person to carry out the requirements in the Ukraine. It was seen as a compliment when they called him the ‘second Stalin’.” (Source: Ian Kershaw, Hitler: 1936-1945 Nemesis)

“The mood at the Führer’s headquarters is very favorable for Erich Koch. Everyone considers him the right man for the job and a “second Stalin” who will fulfill his appointed tasks. ” (Source: Werner Koeppen, pp. 24f. (entry for 19 Sept. 1941))

Götz Aly in “Hitler’s Beneficiaries” tells us of the “liberal borrowing” the Nazis employed from socialist rhetoric:

“Another source of the Nazi Party’s popularity was its LIBERAL BORROWING FROM THE INTELLECTUAL TRADITION OF THE SOCIALIST LEFT. Many of the men who would become the movement’s leaders had been INVOLVED IN COMMUNIST AND SOCIALIST CIRCLES in the waning years of the Weimar Republic. In his memoirs, Adolf Eichmann repeatedly asserted: “My political sentiments inclined toward the left and emphasized socialist aspects every bit as much as nationalist ones.” In the days when the movement was still doing battle in the streets, Eichmann added, HE AND HIS COMRADES HAD VIEWED NAZISM AND COMMUNISM AS “QUASI-SIBLINGS.”

Scholar of fascism A. James Gregor gives us these gems:

What should be recognized at this point is the fact that Mussolini, whatever else he was, was a collectivist, who conceived human beings as social animals. He had learned that man was a communal being from Marx.

By 1938, Mussolini could confidently assert that ‘in the face of the total collapse of the system [bequeathed] by Lenin, Stalin has covertly transformed himself into a Fascist.’

All totalitarianism of the twentieth century were predicated on a systematic, anti-individualistic collectivism. In the case of Marxist-Leninism, the source was classical Marxism. [Giovanni] Gentile had carefully dissected the neo-Hegelian roots of that collectivism. What he found missing in the collectivism of Marx was ethical concern. He sought to provide that concern to the collectivism of Fascism—a collectivism that shared a common intellectual origin with Marxism and Marxism-Leninism.

What some of the revolutionary syndicalists proceed to do was to identify the ‘communality’ of man not will class, but with the nation. The first intimations of a ‘revolutionary nationalism’ made their appearance among the most radical Marxists.

Whether their ideological commitment was to proletarian communism, or the Nordic race, or the restoration of Italy to its proper place in the community of nations, they all chose the hierarchically structured, charismatically led single party state to pursue their ends—a state first fixed in the political doctrine by Fascism.

Gentile’s rationale was neo-Hegelian in origin, the same source out of which Marxism and Marxism-Leninism were to emerge. In fact, Gentile understood Marxism so well that his essay on the thought of the young Marx has not only withstood the test of time, but was, on the occasion of its publication, recommended as particularly insightful by V.I. Lenin.

By the time of the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Marxist theoreticians had begun to evaluate fascism in a totally unanticipated fashion… More than that, as Marxist theorists were compelled to reinterpret fascism in the light of empirical evidence and political circumstances, the fundamental affinities shared by Marxist and fascist regimes became apparent.

The first Fascists were almost all Marxists—serious theorists who had long been identified with Italy’s intelligentsia of the Left.

Fascism… was the socialism of ‘proletarian nations.’

Fascist social welfare legislation compared favorably with the more advanced European nations and in some respect was more progressive.

Fascism’s most direct ideological inspiration came from the collateral influence of Italy’s most radical ‘subversives’ — the Marxists of revolutionary syndicalism.

[Italian] Fascism was a variant of classical Marxism, a believe system that pressed some themes argued by both Marx and Engels until they found expression in the form of ‘national syndicalism’ that was to animate the first Fascism.

Thus, by 1925, both Leninism and Fascism, variants of Marxism, had created political and economic systems that shared singular properties… Both sought order and disciple of entire populations in the service of an exclusivistic party and an ideology that found its origins in classical Marxism… Both created a kind of ‘state capitalism,’ informed by a unitary party, and responsible to a ‘charismatics’ leader.

It can be said, in a qualified sense, that Gentile entertained considerable sympathy for the neo-Hegelian Marxist intellectual tradition.

Fascism never served the interests of Italian business… there is no credible evidence that Fascism controlled the nation’s economy for the benefit of the ‘possessing classes.’

Neither Stalinism nor Fascist totalitarianism would have been possible without the transmogrified Marxism, that infilled both.

In what bizarre universe are these two sister ideologies of radical socialist progressivism opposites?

Hitler and Stalin saw themselves in the other.